Editor’s note: The views and opinions expressed below are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Fight News Australia, its affiliates and sponsors.

2016 was truly a year to be a UFC fan.

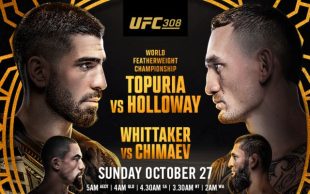

In the space of a meagre 12 months, there were seismic shifts in almost all of the promotion’s weight classes, with 10 new champions being crowned and five new additions to the pound-for-pound rankings*. We saw the short-lived return of Jon Jones, the capitulation and resurgence of Conor McGregor, the likely end of Ronda Rousey’s fighting career, and the birth of potential superstars in Stipe Miocic, Max Holloway and Cody Garbrandt. These and countless other storylines sent MMA media and fans into a frenzy on what felt like a weekly basis, and for better or worse continued to garner mainstream attention.

Outside the octagon, the shifts were even more consequential, as a tsunami of sport-defining developments unfolded with aftershocks sure to continue long past 2017.

At the top of the list was of course the sale of the UFC in July to media conglomerate WME-IMG for a record-setting $4.2 billion, which was attended by an exodus of highly influential figures within the company and intrigue surrounding the intentions of the new (and heavily in debt) owners. The UFC’s new drug policy, administered by the United States Anti-Doping Program (USADA), also proved to be a game-changer, with a seemingly endless list of high profile fighters – including Jon Jones, Chad Mendes, BJ Penn, Cris Cyborg, Lyoto Machida and Brock Lesnar – suspended for using banned supplements.

Interspersed between these major headlines was the legislation of MMA in New York, the introduction of new weight cutting procedures, the passing of long awaited amendments to judicial scoring criteria and the unified MMA rules, and the creation of a female featherweight division.

It was also a year for fighter dissention.

Over the same space of time, two fighters associations have emerged with the explicit aim of improving athletes’ pay and conditions, and literally dozens of active fighters have publicly criticised the UFC for everything from its newfound penchant for interim belts to its capricious matchmaking.

Whilst outspoken fighters are hardly new – who could forget the promotion’s torrid history with the likes of Tito Ortiz, Rampage Jackson, Randy Couture and Jon Fitch– the volume and intensity of fighter criticism, and the fact that much of it is coming from UFC champions, represents a unique challenge to the UFC’s new owners.

Much of the discontent can be traced to late 2014, when the promotion unveiled its new outfitting policy that thereafter required fighters to wear Reebok apparel in the octagon and prohibited in-cage sponsors. Suddenly, fighters who were making six figures in sponsorship per fight were making a poultry $5 or $10K, with notable names such as former lightweight champion Benson Henderson and perennial heavyweight contender Matt Mittrione voting with their feet and signing with Bellator when their UFC contracts ended. Countless others lined up to disparage the new policy, with middleweight contender Vitor Belfort going as far as calling it “slavery” (it’s not) featherweight champion Jose Aldo being even shorter in his assessment of the deal as “shit” (it is) and former heavyweight champion Fabricio Werdum telling Reebok – via an instagram post that ultimately lost him his place on the UFC’s Spanish commentary team – to “suck [his] balls” (they didn’t).

Things kicked up a gear after the UFC’s sale, with a figurative army of fighters immediately calling on the owners to increase the revenue split between the promotion and the fighters such as other sports, which laid the foundation for the aforementioned fighters associations.

First came the Professional Fighters Association (PFA) in August led by sports agent and attorney Jeff Borris, who had represented Nate and Nick Diaz in the past. Flanked by a team of battle-hardened sports professionals and UFC bantamweight Leslie Smith, the PFA appeared to have a comprehensive and eminently plausible plan to become a certified union with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and secure better conditions, including pensions, pay minimums and an independent rankings system. Since their emergence however, the PFA have been faced with significant setbacks, including the loss of Smith and Labor lawyer Lucas Middlebrook after confidential information pertaining to fighters interested in serving on an interim board for the association was leaked to MMAJunkie. More recently, Borris has indicated that unless he received the requisite number of solicitation cards by April for the purposes of approaching the NLRB, he would close up shop in what was surely music to Dana White’s ears.

Next came the Mixed Martial Arts Athletes Association (MMAAA) in November, spearheaded by former champions Georges St Pierre, Cain Velasquez and TJ Dillashaw, perennial contenders Tim Kennedy and Donald Cerrone and former Bellator CEO Bjorn Rebney. Big on star power but small on details, the MMAAA has been relatively quiet since its inaugural conference call, where the association was launched and laid out its three-pronged plan to (1) seek a settlement deal on behalf of former UFC fighters; (2) seek a 50-50 revenue split between promoters and fighters (presently fighters get between 8-15%) and (3) negotiate a collective bargaining agreement for ancillary benefits analogous to other professional sports. In the interim, legitimate questions have been raised about the place of Rebney in the organisation, who struck an accusatory tone when discussing the UFC’s business practices despite having engaged in unscrupulous conduct of his own as a promoter; and spoke dismissively of other efforts to organise fighters such as Borris’ PFA and the Mixed Martial Arts Fighters Association, who are involved in an antitrust lawsuit against the UFC. More recently Kennedy, the Association’s President, has downplayed Rebney’s role in the organisation and reported being embraced “with open arms” by two major MMA gym – so things may be looking up in the near future.

The union “movement” (noting that the MMAAA is not actually seeking to become an official union in the short term) has left a lot to be desired so far, and faces significant and complex barriers to successfully tipping the scales in favour of the fighters. However, the importance of these new organisations, and of the MMAFA who are also lobbying for greater regulatory intervention in the US Congress, should not be understated, nor can the enthusiasm of fighters to improve their conditions be ignored.

More than any time in the history of the UFC, fighters are realising their worth to the promotion and trading on that value to secure better conditions for themselves, with flow-on benefits for their counterparts. The most extreme example of this is of course Conor McGregor, who successfully strong-armed the promotion into giving him a rematch with Nate Diaz last August and used his most recent octagon victory at UFC 205 to publicly lobby for equity in the company, but examples abound of other high profile fighters forging similar rebellious paths.

Champions – amongst them Tyrone Woodley, Michael Bisping and Cody Garbrandt – have abandoned the traditional reverence fighters had for the promotion’s matchmaking and are instead vocally pursuing “money fights”, making it clear that they want a seat at the table when decisions are made that affect their careers and future legacies.

Other big names are agitating to renegotiate their contracts, with Tony Ferguson refusing to his sign his bout agreement for an interim lightweight championship fight until he received the same purse as his opponent Khabib Nurmagomedov; and heavyweight champion Stipe Miocic appealing to the UFC brass to improve his “crappy deal” after learning his most recent opponent, Alistair Overeem, made $200,000 more than he did at UFC 203.

Many are simply becoming more candid about their dissatisfaction with the UFC’s decision, with the class of fighters that could be relied upon to accept the promotion’s terms and fight whoever was put in front of them – the “company men [and women]” – sharply diminishing. A shortlist of perturbed pugilists includes veteran and notoriously soft-spoken middleweight Gegard Mousasi who has vocally complained about his struggle to secure a highly ranked opponent despite his 4-fight win streak and top-5 ranking, implying the promotion is obstructing his path to the title because he lacked star power; former middleweight champion and pound-for-pound king Anderson Silva who accused the new owners of prioritizing entertainment over meritocracy; and welterweight contenders Stephen Thompson (no. #1) and Demian Maia (no #3) who have struck a similarly confused and angry tone in response to news that Nick Diaz – semi-retired and winless since 2013 – was offered a fight against Woodley at UFC 209 when the former had signed a bout agreement weeks earlier and the latter wasn’t even considered.

And then we come to Mark Hunt, the Australian heavyweight and cult hero who last fortnight filed proceedings in the Nevada Supreme Court against the UFC, Dana White and Brock Lesnar in connection with Hunt’s UFC 200 contest with Lesnar in July 2016. Lesnar was controversially awarded an exemption from the USADA pre-fight testing requirements for the bout and was later found to be using performance-enhancing substances, which Hunt is using to support claims that the parties collectively engaged in racketeering, fraud, breach of contract and unjust enrichment. Granted Hunt’s claims are for the most part unsubstantiated, and his legal team must overcome significant procedural hurdles before securing an actual trial. But these obstacles notwithstanding, the fact remains that an active member of the UFC roster – with a high profile fight in March no less – is suing his own company. The best the promotion can hope for is some bad publicity; the worst is a long-drawn out trial (and the re-opening of this can of worms) or an expensive settlement.

So what can we make of this unprecedented mutiny in the UFC’s ranks? And what if anything can the new owners do to steady the ship? The answer to the first question can be answered concisely: it’s a long time coming. The answer to the second is a little more complicated.

Allow me to explain.

The first thing to note is that these aren’t the usual suspects when it comes to UFC criticism – the Jose Aldos or the Randy Coutures who the company could (and did) discredit as ungrateful or duplicitous when they spoke out against perceived injustice. Instead, these are popular champions and surging contenders; men and women who are – perhaps for the first time – beginning to show signs of solidarity and for that reason cannot be conscripted into a narrative that sees the beloved “company guy” (think Chuck Lidell) face off against the maligned and embittered former star (think Tito Ortiz). Fighter unrest has become so pervasive that it is hovering over almost all of the UFC’s marquee matchups, and no amount of PR-spin can insulate the promotion from that reality.

The second is that there are similar themes underlying the otherwise sporadic fighter dissention, most (or all) of which could be addressed by an effective union and/or the expansion of the Ali Act. Don’t like fighter pay? The union will negotiate higher pay minimums, pensions, health insurance and a piece of those television network contracts. Don’t like volatility in matchmaking? The union will negotiate an objective rankings system or the Ali Act will put in place an independent sanctioning body to determine rankings and championship fights. Tired of the promotion’s disproportionate bargaining power? The Ali Act will make them disclose their revenue and end coercive contracts. Want to get rid of Reebok? The union will have a say on contract renewal talks. The list goes on.

None of this lost on WME-IMG and for that reason the company is limited in how much it can reprimand the growing class of fighters who are speaking up. They’re aware that retaliation might provoke a small mutiny or buttress an otherwise underwhelming crusade towards unionization – which puts fighters in the drivers seat.

The third is that even if a union wasn’t a credible threat to the UFC’s hegemony, the very public knowledge that WME-IMG’s purchase of the UFC was financed by $1.8 billion in debt gives fighters unprecedented leverage. A lock-out similar to that embarked upon by players in the NBA might be impossible due to the risk of antitrust liability, but more fighters like Tony Ferguson’s holding out until they get better pay? That’s going to cause some serious headaches, leaving the new owners with the stark choice of increasing their fighter payout or damaging their brand by keeping their stars on the shelf.

In 2017 the UFC’s new owners face a myriad of challenges. Its superstars – the McGregors and Rouseys – are for the most part absent, and the company men and women who the company could traditionally fall back on are nowhere to be found.

Combined with two lawsuits, a fledgling union movement, a mountain of debt and a militia of unsatisfied combatants, literally anything could happen in the next 12 months.

So strap yourselves in. We’re heading into entirely unchartered territory.

* Tyrone Woodley, Stipe Miocic, Max Holloway, Michael Bisping, Donald Cerrone. Based on Sherdog P4P rankings.

Sherdog P4P rankings 3 January 2016

Sherdog P4P rankings 5 January 2017